Curvature is a local notion in a finite geometry that adds up to a topological invariant. This is Gauss-Bonnet. I’m only really interested in curvatures that satisfy this exactly. This does not exclude sectional curvature, the latest venture because sectional curvature integrated over a geodesic sheet is the Euler characteristic of the sheet. Sectional curvature then gives rise to other curvatures like Ricci or scalar curvatures and so to variational problems like the Hilbert action that are not invariant under deformations. I had been flirting for years with Euler characteristic itself as a functional. Maximize or minimize Euler characteristic among all graphs or simplicial complexes or delta sets with a given number of elements looks like an interesting problem but looks very hard, especially in higher dimensions. When looking at the average of sectional curvatures over all possible two dimensional directions integrated over the entire space we get a reasonable discrete Hilbert action. Whether it selects out interesting Einstein manifolds needs to be seen.

In this talk, I did not have lots to say and I looked a bit about adventures in this area of discrete geometry as the question about Puiseux curvature satisfying Gauss-Bonnet had been my first project in this area. (I mentioned the curvature 60 result which was one of my first experiments in this field. If you take a fullerene type graph, then the curvatures add up to 60, where

are the spheres of radius

. After I had to give up on the entropy project (which started in 1987 and ended in 2005), I had been looking for other ventures in math. After trying things in cryptology (one off-shot was a Chinese remainder theorem which I proved in 2005 and which was considered too obvious to be interesting for a referee) or structure of motion (especially in a panorama setting), work which was dismissed by referees with words like “interesting, could appear in a book but not in an article” and “Diophantine stuff” like golden rotations motivated by almost periodic Dirichlet series or almost periodic Taylor series, and the (for me still amazing) result about the cotangent function (which was way too heavy for referees to grasp but which I still find amazing because it is an example of a non-trivial random walk that is exactly computable. I wrote once a bit about that entire theme when giving a talk in 2015 and showing what happens if two extremal topics (golden ratio is an extremal case of real numbers in a Diophantine setting, the cotangent function is extremal in the harmonic analysis case and important as it is related to the Cauchy distribution which is a central limit fixed point in a high risk case and the Maryland model in solid state physics and related to partition functions in number theory, modular forms, fixed points of renormalizations maps, KAM, Green functions, determinants etc, etc. ) Anyway, finite mathematics is a perfect setting for research if one can not rely on your own reputation or friends refereeing you. Once one has seen Gauss-Bonnet principle, it is immediately clear. Once seen, one can not unsee it. It is too trivial even for being published. (By the way, my 2011 article on Gauss-Bonnet-Chern had not even obtained referee report in 2011. The only message an editor has sent me was that “it was not suitable”, meaning of course that nobody even bothered to read it before dismissing it or that the editor could not find anybody who would be willing to read it. I attribute it today also to a culture clash in that most graph theorists at that time looked at graphs as “one-dimensional simplicial complexes” which is not doing justice to the field. Graphs carry very naturally a higher dimensional structure if higher dimensional simplices are present. Whitney already looked at such flag complexes and it is actually what everybody looking at a triangulated space has in mind. ). Maybe discrete Gauss-Bonnet is also too simple: the Euler characteristic

remains the same if the energies

is distributed equally to the vertices in the simplex x. See the last few lines in this handout [PDF]) . Once you have seen the principle of shoving the energy to the lowest dimensional part of space, you can not un-see it. It is just too obvious. But the simplex generating function version

is neat and a bit surprising. I could even teach this in math 1a (single variable calculus) where it appeared in a data project. This was a course where many students have never seen calculus before. What makes discrete curvature really interesting is that integral geometry allows to link it with the continuum and to see that this IS the discrete analog of Gauss-Bonnet-Chern. It is mind-blowing that in the discrete we do not only deal with 2k-dimensional manifolds but that it works for ANY network (finite simple graph) or ANY finite abstract simplicial complex. Discrete differential geometry becomes linked with the continuum differential geometry with Nash: just embed in a higher dimensional space and see curvature as index expectation.

[Apropos “easy” results: The theorem about the infinitude of primes which is obvious once you see that n!+1 must have a factor larger than n, (which was mentioned in the TV series Prime Target in episode 5) or Wilson’s theorem characterizing primes as the integers for which (n-1)!+1 is divisible by n (again which appears in the Apple TV series “prime target” and where my initial reaction had again been that it was “too cheesy” as Wilson’s theorem is even simpler than the little theorem of Fermat (just realize that if n is prime than every number modulo n different from 1 is exactly paired with a number that is its inverse so that one can dismiss all pairs and is left with 1 that is self-dual and that if n is not prime, there is a pair a,b which multiplies to zero making (n-1)!=0 modulo n). Wilson’s theorem is hardly taken seriously by any cryptologists looking for a “prime weapon” … But then I thought also that I’m reacting exactly as these referees dismissing something like my multi-variable Chinese remainder theorem just because it is too simple. (P.S. I had tried to publish the Chinese remainder paper in 2005, revised it in 2012 without trying to resubmit, but in 2015 somebody managed to publish it without mentioning my preprint. That author had previously submitted it elsewhere where I got to referee it and pointed out my work, but that person decided to ignored that and managed to submit and publish it elsewhere without mentioning my paper. The fun of course is not the publication, but the discovery. Nobody can take that from you. For me, discovering something alone without any help and independently is the most fun. It gives you the same kick like climbing “free solo”. It is risky and you can easily die but it is the most rewarding. Apropos fun: I love the series Prime Target also because I have had some adventures in that area because we had to go to yearly WK’s (Wiederholungs Kurse = repetition courses) in the Swiss military, where I had been part also of the cryptology group after transferring from the artillery where I had been driving tanks. Unfortunately, I never made photos from the crypto time (which took place in nice villages like Linden or Oberburg or Effingen , maybe because it was forbidden or because we even had to burn all our material at the end of the course. There were excellent military manuals about number theory for example (a nice yellow book) which were better than all crypto books I could find since.]

Generate[A_]:=If[A=={},{},Sort[Delete[Union[Sort[Flatten[Map[Subsets,A],1]]],1]]];

Whitney[s_]:=Generate[FindClique[s,Infinity,All]];

Curvature[s_,v_]:=Module[{G=Whitney[s]},U=Select[G,(MemberQ[#,v]&&Length[#]==3)&];Sum[{a,b,c}=U[[j]];

k=VertexDegree[s,a]; l=VertexDegree[s,b];m=VertexDegree[s,c]; 1/k+1/l+1/m -1/2,{j,Length[U]}]/3];

Curvatures[s_]:=Module[{V=VertexList[s]}, Table[Curvature[s,V[[k]]],{k,Length[V]}]];

Cat=PolyhedronData["ArchimedeanDual","Skeleton"]; (* A source for 2-sphere manifolds *)

c3=Cat[[3]]; K=Curvatures[c3];Print[{Union[K],Total[K]}];

c4=Cat[[4]]; K=Curvatures[c4];Print[{Union[K],Total[K]}];

c7=Cat[[7]]; K=Curvatures[c7];Print[{Union[K],Total[K]}];

c0=Cat[[11]]; K=Curvatures[c0];Print[{Union[K],Total[K]}];

GP[s_]:=GraphPlot3D[UndirectedGraph[Graph[EdgeRules[s]]]];

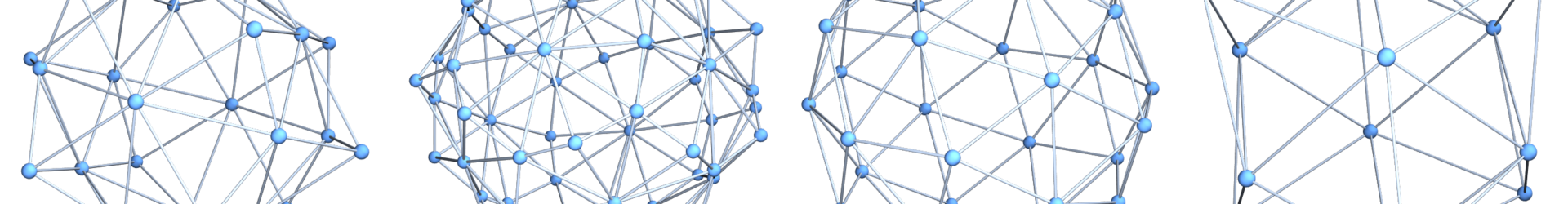

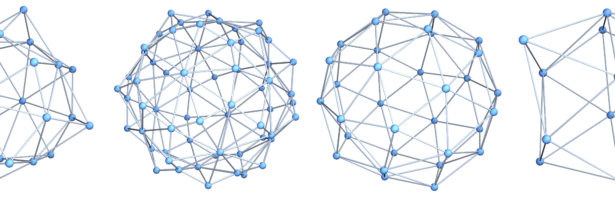

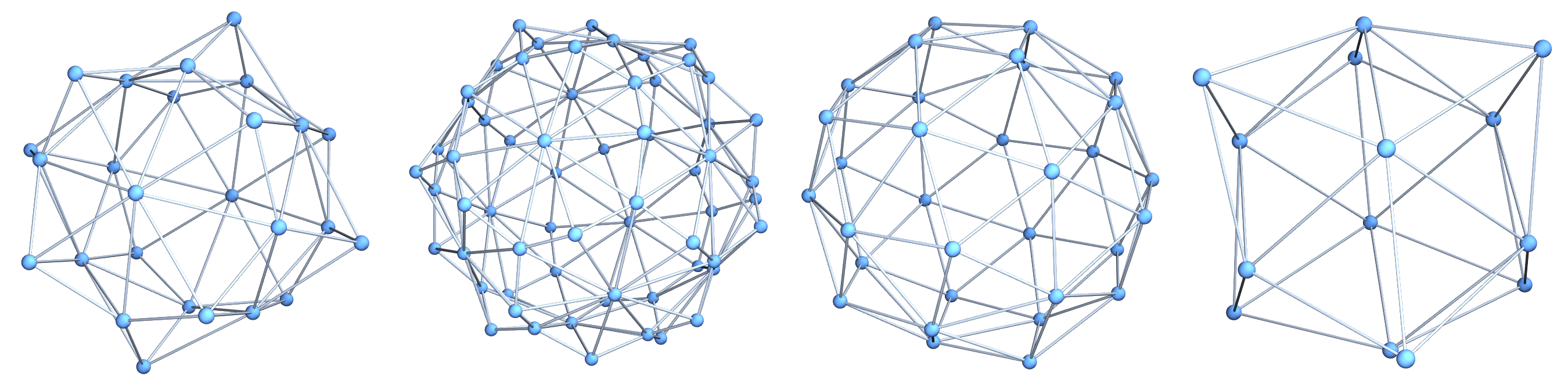

GraphicsRow[{GP[c3],GP[c4],GP[c7],GP[c0]}] (* see graphics Figure 1 above *)

M=13; torus=CirculantGraph[M,Sort[Union[Table[Mod[a^2,M],{a,M-1}]]]];

K=Curvatures[torus];Print[{Union[K],Total[K]}] (* this was a flat Clifford torus *)

rp2=UndirectedGraph[Graph[{1->5,1->7,1->2,1->4,1->8,1->9,2->6,2->9,2->3,2->5,2->10,

4->3,4->5,4->11,4->7,4->12,8->7,8->14,8->9,8->15,9->10,9->15,3->7,3->10,3->6,3->11,5->6,5->12,

5->13,10->11,10->15,6->7,6->13,6->14,11->12,11->15,7->14,12->13,12->15,13->14,13->15,14->15}]];

K=Curvatures[rp2];Print[{Union[K],Total[K]}] (* a discrete RP2 by Jenny Nitishinskaya from 2014 *)

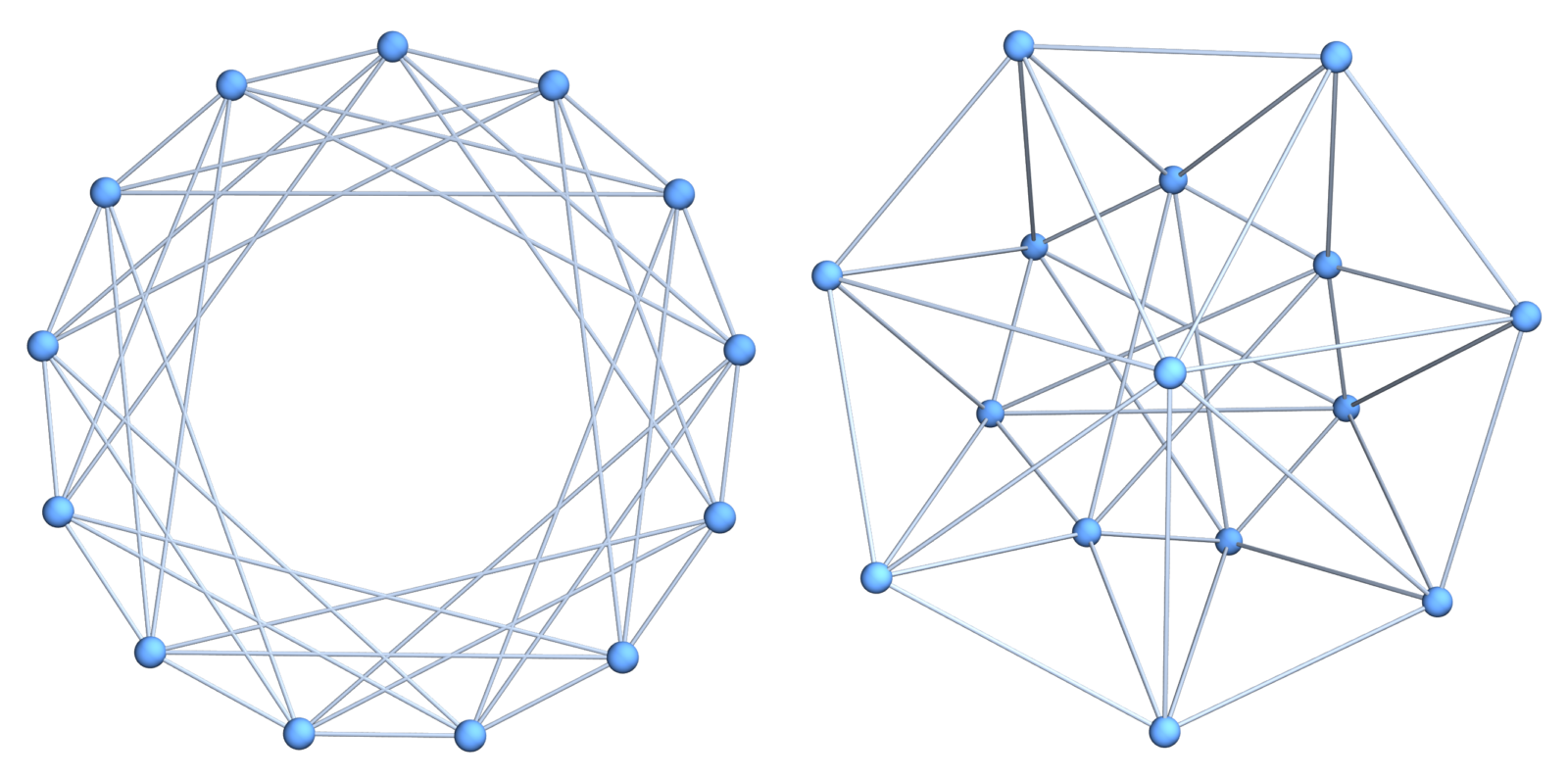

GraphicsRow[{Graph3D[torus], Graph3D[rp2]}] (see graphics Figure 2 above *)